Gateway to the Skies

St. Louis has been a major player in aviation history since the earliest days of flight. By the early 1900s, a popular spot emerged north of the railroad tracks called Kinloch Field (also known as Kinloch Park Grounds).

Originally used as a horse racetrack, it later

transformed into the St. Louis Lambert International Airport we know today. Here are some significant events that happened at Kinloch Field:

- The First Presidential Flight: Back in 1910, President Theodore Roosevelt took the very first airplane ride of his life right there at Kinloch Field.

- Parachute Power: Two years later, in 1912, history was made again when the first successful parachute jump from an airplane happened at Kinloch Field.

St. Louis continues to be a leader in aviation, and its early days at Kinloch Field truly helped things take flight.

Here are some key moments in St. Louis’ impressive aviation story:

- St. Louis Flying Field Takes Flight: In 1920, the Missouri Aeronautical Society leased a field and opened the first airfield in the county, St. Louis Flying Field. This field was the first to use a basic air traffic control system that relied upon controllers on the ground using flags before upgrading to a radio tower in the 1930s.

- Honoring a Local Hero: In 1923, the airfield was renamed Lambert Field after Albert Bond Lambert, a St. Louisan who loved aviation and was the first in the city to get a pilot’s license.

- Lindbergh Makes History: Charles Lindbergh, sponsored by Lambert and other St. Louis aviation enthusiasts, refueled his plane, “The Spirit of St. Louis,” at Lambert Field during his record-breaking solo flight from San Diego to New York City, eventually crossing the Atlantic to Paris in 1927.

- From Lease to City-Owned: After the initial lease ended, the City of St. Louis bought the field, making it the first municipal airfield in the United States in 1928.

- A New Name and a New Era: In 1930, aviation pioneer Richard E. Byrd christened the field “Lambert-St. Louis Municipal Airport.”

- The First Terminal Opens: The airport officially opens its doors to passengers with the

construction of its first terminal in 1933. - A Thriving Airport: By the 1940s, Lambert Airport was a bustling hub with a post office,

airlines, flight schools, and many aviation enthusiasts calling it home.

St. Louis’ early embrace of aviation and its role in Lindbergh’s historic flight helped shape the city’s legacy as a major player in the aviation industry.

St. Louis Readies for Takeoff

The 1920s were a roaring time for aviation, and St. Louis was right in the middle of it.

In the 1920s, the U.S. military realized they needed more airplanes, both for fighting and for keeping the country safe. Then, in 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic Ocean in his plane, “The Spirit of St. Louis.” This amazing feat led to even more excitement about the promise of aviation.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to fly – both in the military and civilian sectors. This created a huge demand for new aircraft to be built. To meet this demand, two aviation companies, Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and Wright Aeronautical, decided to team up, and Curtiss-Wright was established in 1929. This company would go on to be an early leader in manufacturing aircraft for war and civilian use. With this surge in production, St. Louis, with its established aviation infrastructure and Lambert Field, was perfectly positioned to play a major role in the coming war effort..

The combination of the newly formed Curtiss-Wright corporation and St. Louis’ position as a leader in aviation proved to be a winning force that provided significant wartime production.

During the 1930s, Curtiss-Wright leased land from Lambert St. Louis Municipal Airport to build a factory. Initial factory production focused on civilian aircraft. However, by 1939 with World War II looming, the United States recognized the need to increase military production. This led the U.S. government to award Curtiss-Wright a significant contract to build warplanes in St. Louis. To meet this demand, Curtiss-Wright needed more space. They leased additional space from the airport and built a large new factory complex. The first buildings of the factory were built in 1941 with additional buildings as the war went on. The Curtiss-Wright factory in St. Louis was a vital part of the war effort, as it churned out aircraft that helped the United States and its allies win the war.

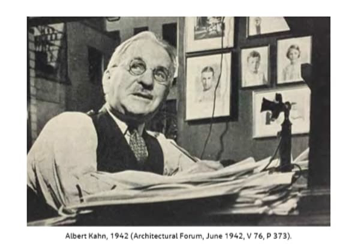

The Architect Behind America’s War Factories: Albert Kahn

Albert Kahn, a Jewish-German immigrant, arrived in the United States at a young age, starting his career as an office boy. But his talent for design couldn’t be hidden. He climbed the ranks, eventually opening his own firm and revolutionizing industrial architecture.

Kahn wasn’t satisfied with the inefficient factories of the time. He envisioned bright, spacious, and efficient buildings. His innovative designs used lots of glass walls and clever layouts, perfect for modern manufacturing. This approach, now known as modern industrial architecture, became his signature style.

During World War II, Kahn’s skills were tested when Curtiss-Wright hired Kahn to design the massive Curtiss-Wright Aeroplane Factory in St. Louis, a symbol of American industrial might. The Curtiss-Wright Aeroplane Factory was the final factory designed by Kahn before he passed away. Kahn’s company was the world’s largest for designing industrial buildings. His work helped shape how factories look today, earning him the nickname “Maker of 20th Century Modern Architecture”. While war factories are an important part of Kahn’s story, his impact goes far beyond. He designed countless factories, auto plants, and other structures across the United States. His focus on functionality and efficiency continues to influence architects today.

Kahn’s story is one of hard work, ingenuity, and the power of design to change the world. His contribution to the war effort and the advancement of industrial architecture is undeniable. The Curtiss-Wright factory is a reminder that even behind the scenes, the contributions of visionaries like Albert Kahn were essential to the Allied victory.

Key Details About Kahn:

Early Life: Born in 1869 in Germany and immigrated to Detroit, Michigan at age 12

Early Career: Trained at architecture firm, designed houses and banks

Innovation: Patented a way to strengthen concrete with steel, allowing for larger, brighter factories

Famous Projects: Packard Motor Car Company Plant, Ford Highland Park Plant, Curtiss-Wright Aeroplane Factory

Factory on Overdrive

The Curtiss-Wright factory in St. Louis played a key role in supplying airplanes to the U.S. military during World War II (1941-1945). The war caused a worker shortage, so Curtiss-Wright became a leader in training women for factory jobs. Women trained to be welders, riveters, inspectors, and assembly line workers. The company also encouraged people of all backgrounds to apply for training programs. Black and White workers were segregated from each other at the St. Louis plant. Workers were assigned to work on separate floors in racially separated production units.

During World War II, the Curtiss-Wright factory in St. Louis went from building airplanes for fighting (A-25 dive bombers) to building airplanes for transporting people and supplies (C-46 Commando). The C-46 Commando was originally designed to carry passengers, but it was turned into a twin-engine plane that could haul cargo and troops during the war. After the war, most C- 46s continued to be used for cargo instead of passengers. The St. Louis factory also produced numerous AT-9 and CW-22 trainer aircraft which were instrumental in training scores of new pilots entering the war effort.

After World War II, Curtiss-Wright planned to convert their St. Louis factory to build civilian airplanes. They wanted to make a passenger version of their military C-46 transport plane, called the CW-20. However, demand suffered as a result of the influx of used military aircraft that flooded the market after the war.

Because of this, Curtiss-Wright gave up the factory in July 1945. The government took over to finish building any airplanes already ordered. In 1948, the factory wasn’t sold, but instead leased to a new company called McDonnell Aircraft. This company had already been using smaller buildings at Lambert Airport.

Secret Weapons and Space Dreams

McDonnell Aircraft, started by James McDonnell in 1939, also built airplanes in a factory near Lambert Field. Many significant aircraft were produced at the location, including the XFD-1 Phantom. The XFD-1 Phantom was the first jet fighter to land on an aircraft carrier. Following World War II, the company got even busier with orders for more jets from the military.

After the war, McDonnell kept building successful fighter jets in St. Louis, like the F2H Banshee. The Banshee was so successful, the road adjacent to the factory was renamed after it – Banshee Road.

McDonnell continued to develop and produce world renowned fighter jets like the F3H Demon, F- 101 Voodoo, and F-4 Phantom II throughout the 1950s and 1960s. These jets saw extensive service during the Korean War and Vietnam. In particular, the F-4 Phantom II became one of the most significant military jet fighters of the 20th century, with more than 5000 being produced. It played a pivotal role in Vietnam and has been in operation with many countries.

The St. Louis factory also helped NASA launch astronauts into space. In 1959, McDonnell was selected by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to produce spacecraft for the Mercury and Gemini programs. Space capsules for both programs were assembled in white rooms at the St. Louis facility.

In 1966, McDonnell joined forces with another big aircraft company, Douglas, to become McDonnell Douglas. This powerhouse company continued building famous fighter jets in St. Louis like the F-15 Eagle, F/A-18 Hornet, and AV-8B Harrier vertical takeoff and landing jet which were relied upon in recent conflicts like the Gulf War and Afghanistan.

Soaring into the Future

At the dawn of the 21st century, Boeing set the runway for future dominance in St. Louis with a $250 million expansion. Their centerpiece? A state-of-the-art facility to assemble the game-changing. Joint Strike Fighter. But Boeing’s vision wasn’t just about one plane. They were plotting an entire mission.

Fast forward to today, and Boeing’s St. Louis chapter is still being written. Their sights are set on the next generation of aerial warriors. A brand new 1.1 million square foot facility is under construction. This investment hints at Boeing’s commitment to innovation and their ambition to stay at the forefront of defense technology.

One thing remains constant: Boeing’s legacy in St. Louis. It’s a story that began with the pioneering spirit of Curtiss-Wright, and it’s a story poised to take flight with groundbreaking projects on the horizon. St. Louis and Boeing – a partnership that promises to keep the skies abuzz with innovation for years to come..